Prospective Residence Assistants can expect falling grades, decreased mental health, and constant work

Within my first month of university, I decided to become a resident assistant (RA). I made the decision because I had the dream of helping new students feel welcome and cared for at Mount Allison. In retrospect, it was one of the worst decisions I’ve made.

After submitting my application and going through the interview process, I was convinced that the $3,000 stipend and the experience were enough of a reward for my service. I fully believed that the residence dons and Student Life would be there to provide solid support for me and my fellow naive RAs. That quickly changed after RA training began in August.

The RA training lasted a full week. The training was about 90 per cent on how to be a good student, and 10 per cent for how to actually be an RA. That week, I learned how evasive Student Life is. I distinctly remember an RA trainee asking whether the names of students who have a known history of misconduct and are banned from certain residence buildings will be shared to other residence teams. The spokesperson spent around 10 minutes asking for clarification when the question simply demanded a “Yes” or “No” response.

Throughout the year, I witnessed the mental health of my colleagues deteriorate alongside mine. What disappointed me was the lack of resources available to RAs coping with having to tell residents to stop smoking weed in their rooms, or having to take care of the same few drunk residents every weekend. By the end of fall term, it was clear that Student Life was too timid to evict problematic students from residence – or worse, they would simply relocate those students to another residence. The countless incident reports that we wrote were like screams into the void. They seemed like they were there for our benefit, but had no real impact on challenging situations.

In March, I was asked to quit the RA team. The dons phrased the request as advice, suggesting that I voluntarily leave the RA team for my personal mental health. I initially did not want to leave, but then they informed me – for the first time – that I had been underperforming my duties for months. At that point I did decide to resign. I knew there was no way I could work with a residence team who saw my mental health decline and maintained silence instead of intervening.

A year later, when I spoke with my former colleagues, I was relieved to learn that I was not the only one. I haven’t spoken to a single RA who did not experience a deterioration of their mental well-being or their grades that year.

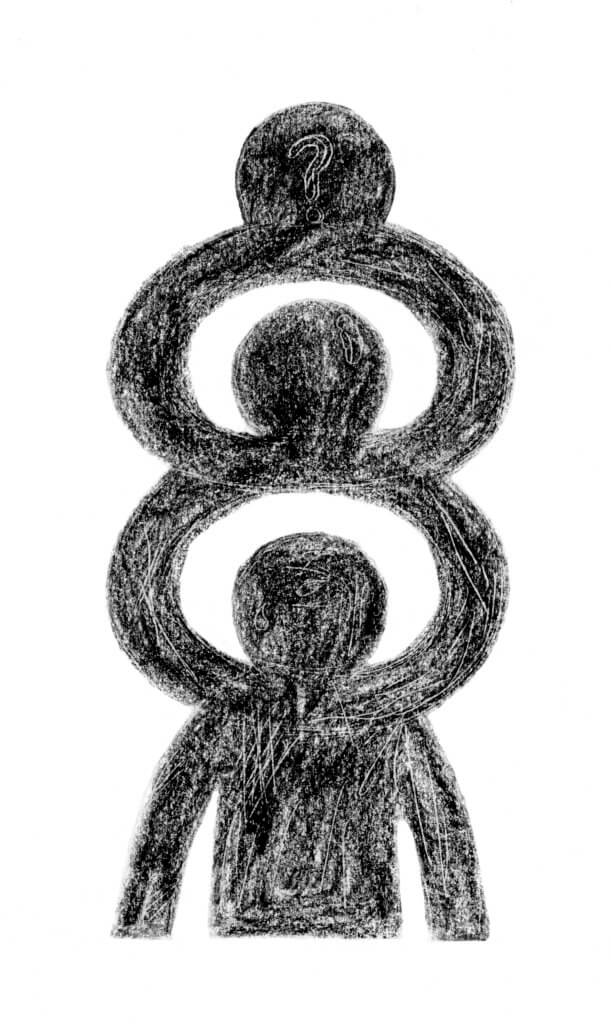

What did I learn from my experience? I sure as hell learned that capitalist structures lead employers to exploit their workers as much as they can. I learned that living in your workplace means work schedules are a lie and work is 24/7 as long as you are in the building. I learned that no matter how healthy you are when you begin the job of an RA, the disrupted sleep schedule and lack of support will wear away your mental health (and consequently your grades, and sense of self-worth). A few positive things did come from this experience; namely, knowing that mutual suffering can lead to a stronger sense of community, and that one does not need to be loved by everyone to be happy.

If I had been able to foresee where I am now, I would not have chosen to be an RA. That meager $3,000 was not worth the year of poor mental health, the $400 ambulance ride to the Moncton psych ward, and the disrupted sleep schedule from which I am still trying to recover.